A Poor Journalists's Text Mining Toolkit

08 June 2016

How can you search and analyze collections of documents on your own computers with simple tools? At last weekend’s DataHarvest, Robert and I ran a workshop to answer that question. As people were seemed interested, here’s a write-up of the two key tools we worked with: Apache Tika for content extraction and regular expressions in Sublime Text as an advanced search tool.

So, here’s the scenario: a source has given you a USB drive, filled with all the proof you need for a great story. Or, perhaps, you used DownThemAll!, wayback machine downloader or wget to grab a bunch of documents from a government web site. In any case: we’ll assume that you’ve got a folder docs you want to sift through! (If you don’t, here’s something to play with: a collection of all the sanctions issues by the European Union.)

What’s next? You’ll probably to search the documents for the names of people and companies, find mentions of dates to construct a timeline, or perhaps you’ll want to search for details like bank account numbers or email addresses?

Of course, you can go and buy NUIX for a few thousand bucks. Or you can try to find out which desktop search engine is the least crap (hint: they all are). Before you do these things, though, why not try how far you can get with a few free, simple tools?

Converting documents to text

The first hurdle you’ll have to overcome has to do with how computers store data. When you make Word documents, PDFs, presentations or spreadsheets, the program doesn’t just need to store text. It also has to keep a lot of information about layout, who’s been editing what and so on.

To store this data, applications encode documents in complex file formats. This makes it hard to search a many of those files at once without opening each using it’s own program. To do that, we’re going to convert all of your source documents into plain text documents: files that contain nothing but text - no layout, no track changes, no images.

Apache Tika does just that. It’s a Java program that recognizes many types of documents and pulls out the text into a new file. It’s also the engine that ICIJ used to make the Panama Papers accessible.

In order to use it for yourself, you’ll need to know a little bit about how to use your computer’s command line prompt. On a Mac, that’s the Terminal. On Windows, it’s cmd.exe (the DOS prompt). I recommend you learn how to visit a particular directory, and how to see what’s in a particular folder. Here’s a tutorial for the Mac and one for Windows. There’s also session notes from Annabel’s DataHarvest workshop about command-line data processing.

Before Tika can do it’s magic, you also need to install the Java Runtime Environment from the Oracle website. Once it’s installed, download the tika-app file from Tika’s home page. Put it in a directory with a memorable path, e.g. C:\tika\tika-app-1.13.jar on Windows or /Users/yourname/tools/tika-app-1.13.jar on a Mac (the version number might differ, adjust for that).

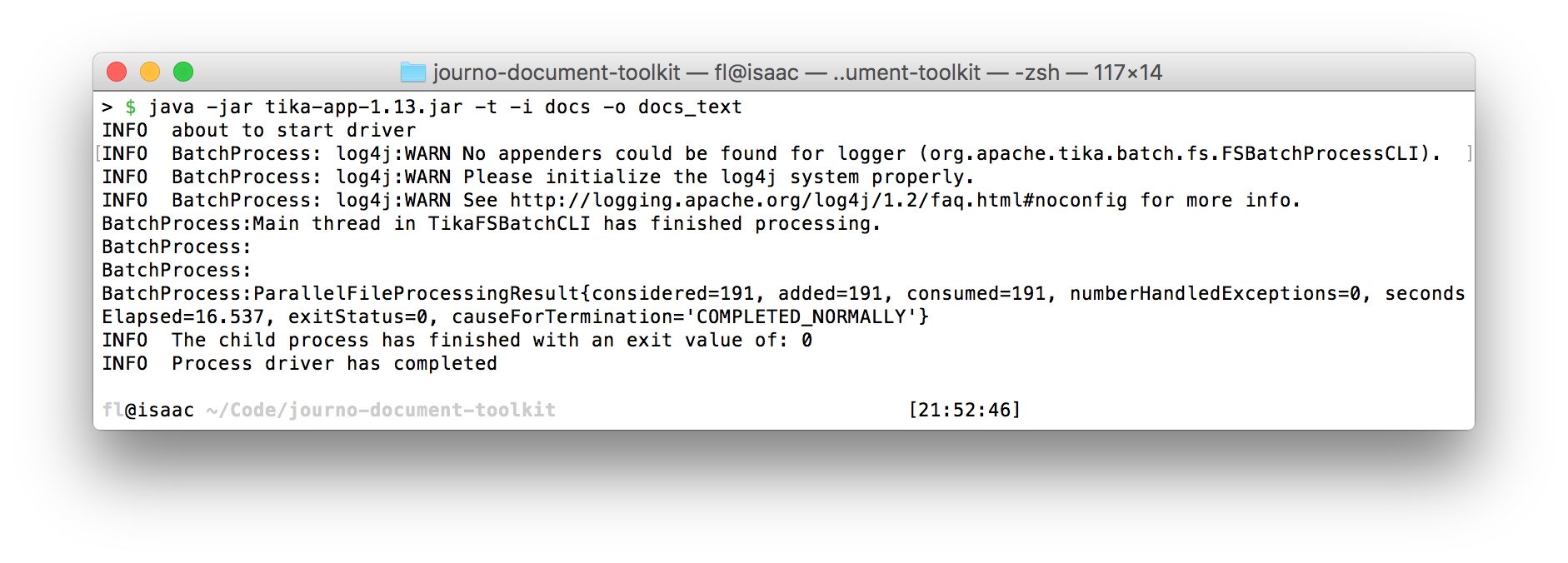

Then you can run Tika like this (the dollar sign is to symbolize a command prompt on a Mac):

$ java -jar /Users/pudo/tools/tika-app-1.13.jar —help

The bit up till tika-app-1.13.jar is just to run tika. After that, you can give a number of options that instruct the tool about the specific operation you want to run. —help is a special option to show you the help text about all the other options.

Based on the output of -help, you can devise new commands, like:

$ cd /Users/pudo/project/

$ java -jar /Users/pudo/tools/tika-app-1.13.jar -t -i folder_with_documents -o output_files_folder

The -t means: convert the files to text. After -t, the second option -i is followed by a directory name and gives the input directory with the original documents. Finally, -o is followed by the name of an output directory for the resulting text files. This will be created automatically.

Once you run this command, it will generate a new folder (documents_text) with all the documents converted to plain text. If you also want to look at the metadata (author, …), you will want to run something like this instead:

$ java -jar /Users/pudo/tools/tika-app-1.13.jar -m -i folder_with_documents -o output_metadata_folder

This will again create a bunch of text files, this time with metadata like the author, creation date and size for each document.

Note that this by itself does not handle images and image-based PDFs. For that, you’ll need to install Tesseract, an OCR tool. I haven’t found a simple write-up for how Tika and Tesseract work together yet, hopefully I’ll get around to that soon. If you’re feeling lucky, here’s a page about it.

Searching for patterns

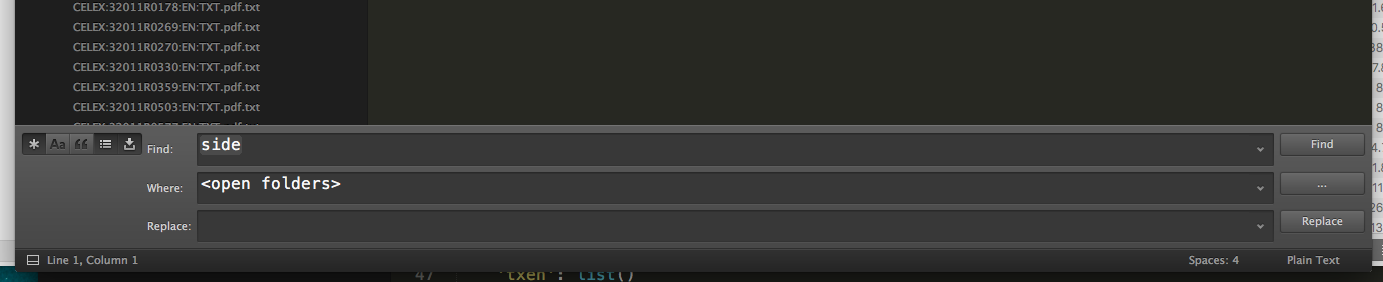

After running Tika, you’ll end up with a folder full of text files, each named after the PDF, Word document or Powerpoint from which they’re extracted. Now, you’ll probably want to search them. For that, rather than using a fancy search engine, we’ll use a text editor, Sublime Text. You can download it for free.

What makes Sublime different from a program like Word is that it’s specialised in dealing with plain text files without any layout or other binary content (try opening a Word or PDF file in Sublime, it’ll show up as a messy set of random letters and numbers).

Once you’ve installed and opened Sublime, you’ll see a dark gray window. Click File > Open... and select the output folder generated by Tika. A sidebar will pop up and show you a list of all the extracted files. Next, select Find -> Find in files... from the main menu. A set of controls will show up at the bottom of the window. Those allow you to search across all files. Try it out by pressing the ... next to the Where field, and selecting Add open folders. In the Find field, you can type in any search term and see a list of matching documents show up in the window above.

After you’ve familiarised yourself with this search tool a bit, you might want to do more advanced searches: find mentions of dates, filing numbers, passport or bank account numbers. To do this, we’ll use a mechanism called regular expressions (close friends also call them RegEx, or RegExp) that lets you describe complex patterns in a piece of text.

In this context, a pattern is understood as an abstraction of what a piece of text looks like. Instead of searching for the date 23.6.2016, a pattern can express an abstract idea of what dates look like: one or two numbers, followed by a full stop, followed by one or two numbers and a full stop, followed by four more numbers.

This gives you a fairly powerful mechanism for pulling structured data out of mountains of text, just by making a recipe for what patterns the text follows. What’s even better: regular expressions are a standard that works in many programs, such as Word (they call it “wildcard search”), LibreOffice, Open Refine, Excel and some advanced online search engines.

What’s the drag? They look horrible. Regular expressions usually end up reading a bit like a three-legged cat tried swing dancing on your keyboard. If you can get over that, the world of text files is your oyster.

Ready? Press the little Asterisk (*) icon on the left-hand side of Sublime’s search bar to activate regular expressions mode. As you do this, you may want to also open the website Regexr in a browser: it’s an online tool that let’s you test a regular expression in a visual way, which can be really helpful.

Optional text

The first thing we’re going to look at is making text optional using patterns. Let’s say you’re working with the EU sanctions documents I linked above, and you want to find all mentions of terms such as “terrorism”, “terrorist” etc. You search for those using this regular expression:

terror.*

This will match all lines that contain “terror”, “terorrism”, “terrorist”. You’ll note the little dot and asterisk at the end. Those are regular expressions operators: the dot means “match any character”, the asterisk says “repeat the previous pattern many times”. It’s important to understand that these wildcards apply to individual characters - they have no notion of words.

Escaping

What if you wanted to actually find a full stop, not use . as a wildcard? In this case, you need to put a backslash in front of it, to escape it:

terror\.

This will find the phrase “terror.”, but not “terrorism”. When I write regular expressions, most of the mistakes I make relate to escaping in some way - so be careful in thinking about this.

Character groups and ranges

You may notice that our “terror” search actually highlighted the entire rest of each matching line, not just the word “terrorism”. That’s because the . wildcard also matches spaces and punctuation. To get match only a single word, you may want to use the following instead:

terror[a-z]*

You can read the square brackets as “any of”: find the text terror followed the lowercase letters between a and z. The asterisk still makes sure you’ll match more than once character. You can also put other characters into the square brackets:

+1-\([0-9]*\)-[0-9]*-[0-9]*

This is an incredibly cruel attempt to match American-style phone numbers like +1-(800)-555-2468. I’ve had to escape the round brackets with backslashes (\), because they also have a meaning in regular expressions. Pretty powerful, right?

Let’s refine this. Instead of allowing any number of numbers in the phone number, I want to specify some lengths. Here’s what that looks like:

+1-\([0-9]{3}\)-[0-9]{3}-[0-9]{3,5}

The curly brackets mean “find n matches”: in the first two instances, I’m looking for exactly three numbers ([0-9]{3}), while the third example specifies a range: [0-9]{3,5} reads as “match any number that has between three to five digits”.

If you think this looks crazy: you ain’t seen nothing yet.

Meta-characters

While the square brackets are quite useful, it can be cumbersome to write out [0-9] every time you want to find a number. Instead, you can also use some shorter aliases that mean the same thing: \d means any decimal, \w means any character that we’d expect inside a word (something like [A-Za-z0-9]), and \s means anything similar to whitespace (including newlines). These are called meta-characters. Our phone number pattern could therefore look like this:

+1-\(\d{3}\)-\d{3}-\d{3,5}

Or, for the terror example:

terror\w*

Matching dates

Here’s an exercise: can you make a regular expression that matches a European-style date like 23.6.2016?

I’ll just wait here…

Kudos if you ended up with something like this:

\d{1,2}\.\d{1,2}\.\d{4}

I had to escape the dots (because I didn’t want anything to match that space) and define ranges for both the month and day sections.

The best patterns are the ones which are the most specific. If you look at months, for example, the numbers only go up to 12. You could thus make your regex more specific:

\d{1,2}\.1?\d\.\d{4}

The middle section here reads “maybe (?) a 1, followed by a single other decimal”. Can you do the same for the days of the month? Hint: you’ll need some square brackets for this one.

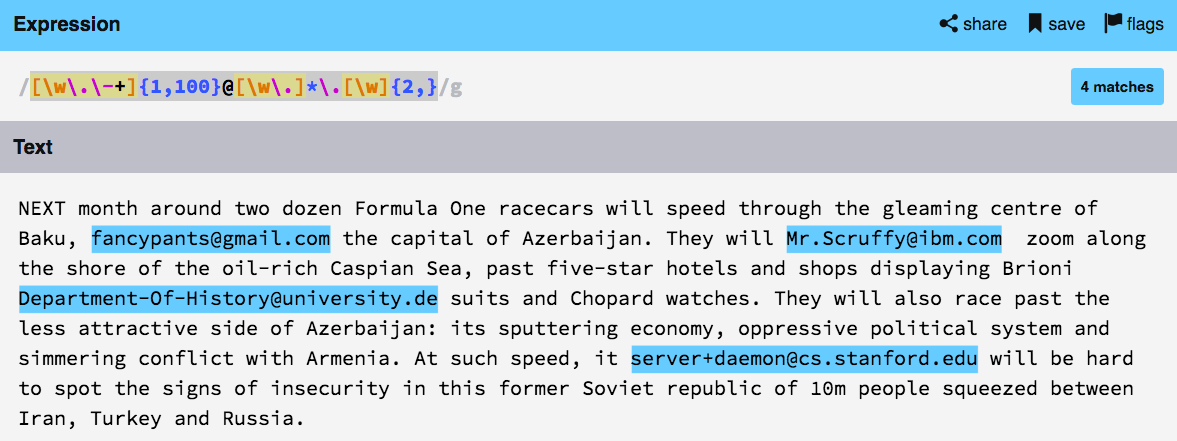

Matching emails etc.

Here’s the good news: you’ve already got most of this and you can do some pretty awesome stuff.

Take a moment to develop a pattern for email addresses by putting a few examples into the text field of Regexr and modifying your pattern until all of the match. Here’s some valid email addresses:

fancypants@gmail.com

Mr.Scruffy@ibm.com

Department-Of-History@uni-versity.de

server+daemon@cs.stanford.edu

There’s all kinds of crazy stuff going on here: email addresses are notoriously hard to make patterns for. But for day-to-day use, something like this might be good enough:

[\w\.\-+]{1,100}@[\w\-\.]*\.\w{2,}

What’s neat about this is how it combines meta-characters (like \w) with square brackets to make more complex character classes, e.g. [\w\.] - “all in-word characters, dashes and dots”.

Groups and alternatives

Before we close, I want to introduce you to one final feature of regular expressions: groups. Groups are formed using round brackets and bundle smaller patterns into units. Here’s an example that matches credit card numbers like 1111-2222-3333-4444:

(\d{4}-?){4}

You can read it as: “Make a group that contains four decimals, optionally followed by a dash. Then repeat this group four times.” Magic. Here’s another:

(na){2,} Batman!

Before things get too silly, a final pattern operator: the “or” pipe (|). It can be used for some trans-atlantic pattern matching:

anonymis|zed

It becomes really powerful only in combination with groups, though. Here’s an example that could be used to parse a parliamentary hansard for speeches made by the chairperson:

(Mr|Mrs|Lord|Lady) Speaker( said)?: .*

There’s a lot going on here: we’re looking for any of the personal prefixes, making the part around ‘said’ optional (using the ? operator) and then allowing for any further text after the colon.

Congratulations: you are now a regex ninja. As with any skill, the routine comes with use - so try to make a few additional expressions on your own. Finding amounts of money, references to legal codes, passport numbers: they’re all useful and can yield surprising results.

Further reading

Conclusion

If you’ve made it this far, chances are you’re a true beliver anyway: this stuff is powerful and can help dig through piles of documents and find very specific patterns and data points. It’s worth spending a bit of time training regular expressions, they’re an incredibly powerful tool that works in a surprising number of places.

While this little toolkit of Tika and Sublime probably isn’t the answer for any big research project, I wouldn’t be surprised if it actually came in useful in smaller, day-to-day investigations. Let me know when you use it, and don’t hesitate to ask any questions via E-Mail!

This post is intended to teach a bit about the command line, Tika, and regular expressions because it’s fun and interesting. If you actually need to deal with a sensitive leak, you might also want to try out Open Semantic Search, or work with a techie.