A little tour of aleph, a data search tool for reporters

29 June 2016

In a short story by Jorge Luis Borges, the Aleph is a point in space that contains all others. To those who see it, it presents the entire universe at once - an investigative reporter’s dream.

Over the past six months, I’ve been working for OCCRP to productise a tool named after this mythical object. It’s based on a prototype I hacked up as part of my 2014 Knight Fellowship, and it has now grown into a data research tool as part of the Investigative Dashboard.

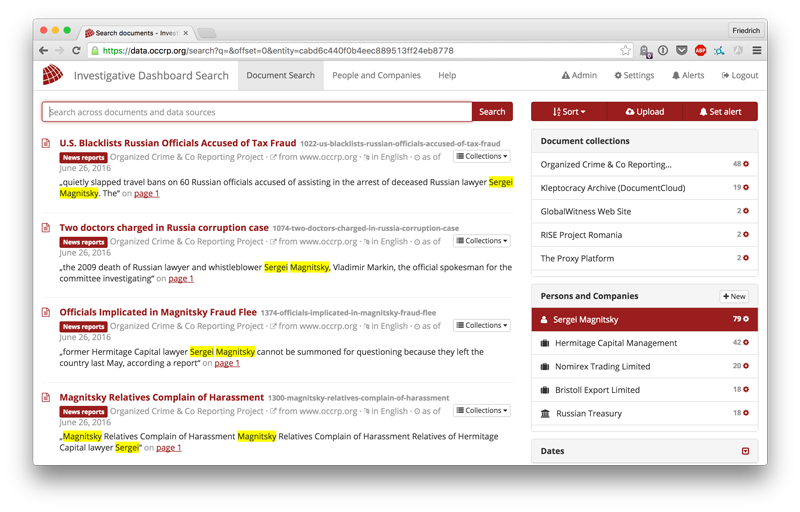

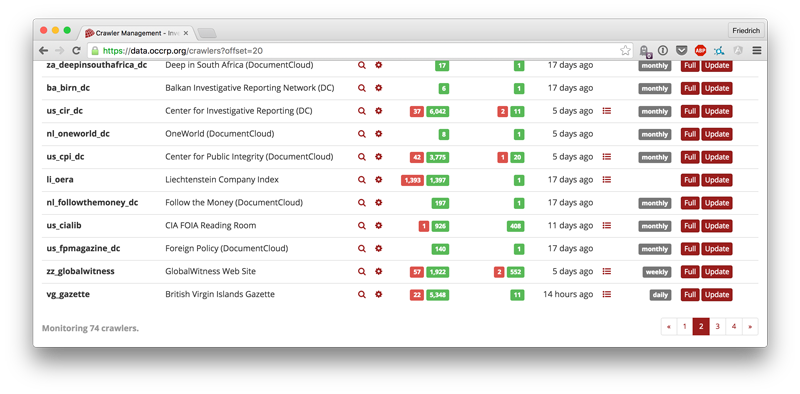

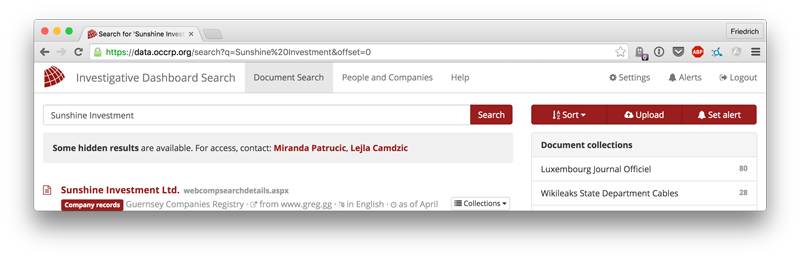

At it’s base, Aleph allows users to search through large collections of documents and data tables. On ID Search, over 100 sources include material as diverse as the Kyrgyz companies register, the US State Department cables, the Gazettes of Luxembourg, Liechtenstein, Switzerland and many other countries, or the UK parliament’s inquiry into the death of Alexander Litvinenko.

What’s more, anybody can upload their own private document collections - whether they are documents, databases, scans, or e-mail archives. Aleph will make them searchable for anyone who is granted access. It will also cross-reference documents with extensive watchlists composed of the world’s sanctions lists, wanted criminals, national politicians and persons and companies that have been investigated previously.

Increasingly, Aleph also extracts structured details from documents: email addresses, phone numbers, web addresses are supported now. Further data points like bank accounts, VAT IDs, dates and monetary amounts will be added soon to give users ever more ways to dissect and filter the data and find what they need.

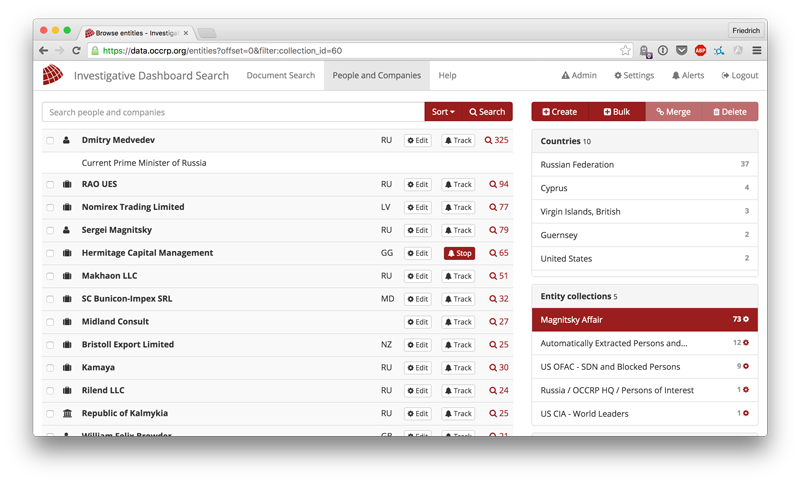

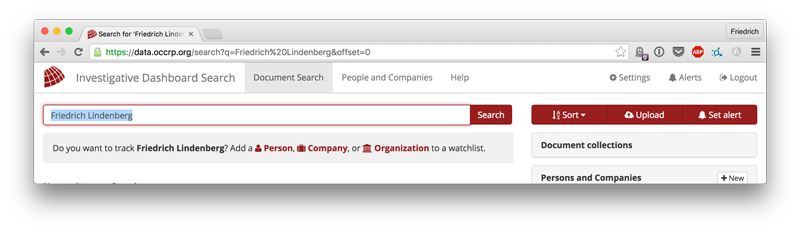

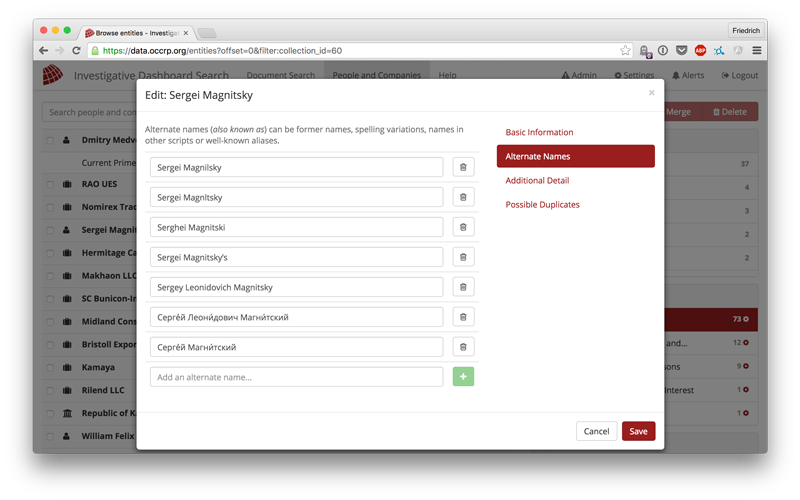

Custom watchlists can also be created by reporters to keep track of individuals and companies in a systematic way, so they can be notified whenever new mentions are found in uploaded documents, or in the growing number of public data sources which Aleph automatically harvests on a regular basis.

Building investigative memory

Aleph is designed to support people who do investigative research on two levels: in their day-to-day work, and in a more strategic sense. Day to day, it is a research tool that finds your next lead or helps you analyze a pile of documents from a leak when you are right in the middle of an investigation.

But in the long run, it’s also a way for reporters to build up a living archive - both of source material, but more importantly of structured information about the people and companies that they are interested in. This juxtaposition of structured data and unstructured documents is the bet that we’re making with Aleph.

This helps individuals and organisations to keep track of what they know and what they need, but it can also be a way to create collaborations between researchers. Using the “peek” function, the tool connects those who hold private documents with those who searched for terms within these documents. This will hopefully also link into ICIJ’s decentralised DataShare tool, which has similar objectives.

What’s the verb for ‘data’?

The key in designing Aleph, however, is to serve practical research needs: finding key documents quickly, getting alerted to new information, or mapping out the major actors in a particular story.

Experimenting with how these can be made into interactions that people will routinely engage with is the hardest aspect of this project. Few investigators will adopt data-management tools if there is not a concrete and immediate pay-off in terms of additional insights that are not trivial.

For me, aleph is also the next step in a learning process that I started with Grano, an influence mapping tool. Aleph represents a more task-focussed, incremental approach towards to making a practical toolkit for investigative reporting.

Of course, it is also free software, which is used both by the ID team at OCCRP, and by OpenOil’s Aleph project, after originally being prototyped at Code for Africa. We’d love to see more organisations and companies adopt it and contribute their own features.