Grano advanced queries, and Linked Data

01 September 2014

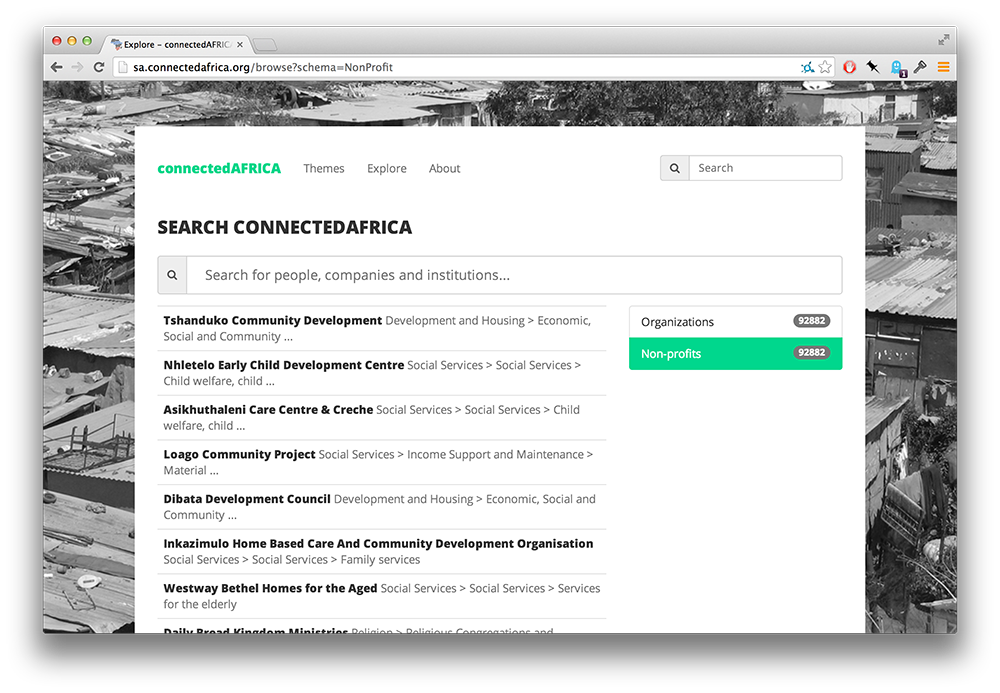

At its current stage of development, grano has achieved some level of maturity as an influence mapping toolkit. We’ve got a great workflow for importing raw data, and we’re running a number of different sites off the backend. A new web interface, to make the application more accessible to non-technical users, is in the works.

So it’s time to look at the next big challenges: building out the way in which grano lets journalist ask complex questions of their data, and improving the handling of source and quality metadata. As I’ve pointed out on IJNet, both of these are essential: having a big bunch of integrated data is cool, but only when you have a tool that lets you interrogate those relationships does it become a real journalistic asset.

</a>

</a>

Unfortunately, the questions that journalists might want to ask against influence networks are often recursive: “show me all the family members of politicians who work for organisations that receive government contracts”, “show me what connects these people to each other”. These are the exact type of query that make relational databases cry.

After producing a proof-of-concept query tool based on grano’s relational backend it became clear that a more flexible approach was needed: queries would easily take seconds, some would eat up all server memory. From this point on, there are two choices: use additional backends to satisfy different types of queries; or migrate to another data model entirely.

Thankfully, the amazing Jun Matshushita was thinking through influence mapping technology choices at the same time, and we had some interesting discussions on graph databases on GitHub. He convinced me to have another look at RDF/Linked Data as a storage mechanism. Unlike, for example, Neo4J, RDF has a variety of ways for attaching provenance to individual statements - a must-have for applications that integrate data from a wide range of sources to find evidence for misconduct and corruption.

At the same time, there is still a total lack of mature (Python) tooling around linked data. This was true when I first experimented with the stuff in 2010, and many libraries haven’t received a single commit since then. Documentation for routine tasks is non-existent, and the standard Python RDF toolkit, rdflib doesn’t actually connect to the vast majority of available triple stores.

It is clear that nobody is using Python and RDF to build web applications. Ironically, people on public-lod seem to believe that the main challenge to broader adoption of linked data is producing the stuff. In truth, your problems really start when you have RDF data and need to store, query and export it in anything other than Java.

Even so, I managed to get another proof-of-concept of my experimental query API implemented, this time running on top of an RDF-converted copy of the data. The surprise: using Apache Fuseki’s backend was even slower than a SQL database for graph traversal, queries would easily take twice or three times as long as their relational equivalent. I’m sure that I haven’t tuned my queries very well, but performance seems to be degrading proportionally to the size of the dataset. And while other triple stores may be somewhat faster, it’s becoming clear to me that this route isn’t leading anywhere. What’s left is a set of open questions:

- Who out there is still building Python tools that use RDF and can talk about making it work?

- How does one connect to triple stores like Virtuoso and Stardog from Python in meaningful way, without having to write a complete binding for even the most trivial operations?

- What are good ways to

EXPLAIN ANALYZESPARQL queries and to get a sense of where their complexity is? - If triple stores are slow when aggregating data and doing distinct counts, how can you get multiple solutions for a query, but limit the number of entities they relate to?

So, it is now time to bring grano into split brain mode: use the existing relational database to store provenance and data quality information, while keeping a simplified data model in Neo4J to enable the types of recursive queries that our users need. As always, I need lots of help to hack out the new Neo4J query API: not only to make sure data is synchronised between the two data stores, but also to experiment with query endpoints that might enable interesting journalistic questions and cool data visualisations.