Data doesn't grow in tables: harvesting journalistic insight from documents

15 May 2015

When we discuss data journalism, we often tend to think of nicely formatted spreadsheets full of financial data or crime stats. Yet most journalistic source material does not take the form of tables, but it comes in messy collections of documents, whether on paper, or scraped off a web site.

Over the last few months, I’ve worked on a few such projects, for example with OpenOil on mining SEC filings for oil contracts, or with the ICIJ to find World Bank documents on project-related resettlements. In the process, I started to develop a set of Python libraries for document mining, and, eventually, a web-based document/entity search tool called aleph.

I’ve also spoken about document mining for journalists, including this presentation at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia:

While each document mining project that I’ve been involved with has very custom needs, my goal has been to construct a set of re-usable applications that allow for fast and reproducible processing of documents.

A Python-based document processing toolkit

Two Python libraries, archivekit and loadkit, form the core of this: archivekit provides an abstraction for the storage of source documents, making sure that the original document is stored on Amazon’s Simple Storage Service alongside any cleaned-up and converted versions of the same file.

loadkit builds on top of this layer by enabling users to configure custom document processing pipelines with support for text extraction (including OCR), normalisation and filtering. Since loadkit is also used by an updated version of OpenSpending, spendb, to manage structured source data, it also supports extracting and normalising data from spreadsheets.

A third library, scrapekit, helps to structure the process of downloading large online collections using custom scraper scripts.

Together, these tools make it very easy to extract all documents from a web site, bag and tag them as evidence, and to convert them into plain text for further analysis.

aleph, an experiment in entity-based document mining

With this foundation in place, I started developing another layer of tooling aimed at non-technical investigative journalists, rather than developers. The expectations of researchers were usually quite simple: most requests focus on searching a set of documents to generate leads that would then be checked by hand. Advanced queries would involve drilling down to relevant sub-sets using document metadata and mentions of dates, places and entities within the documents.

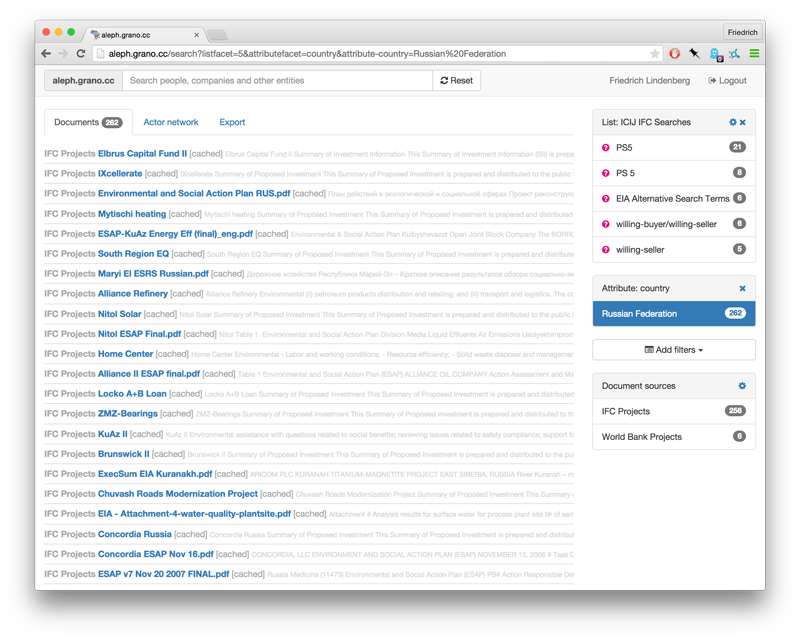

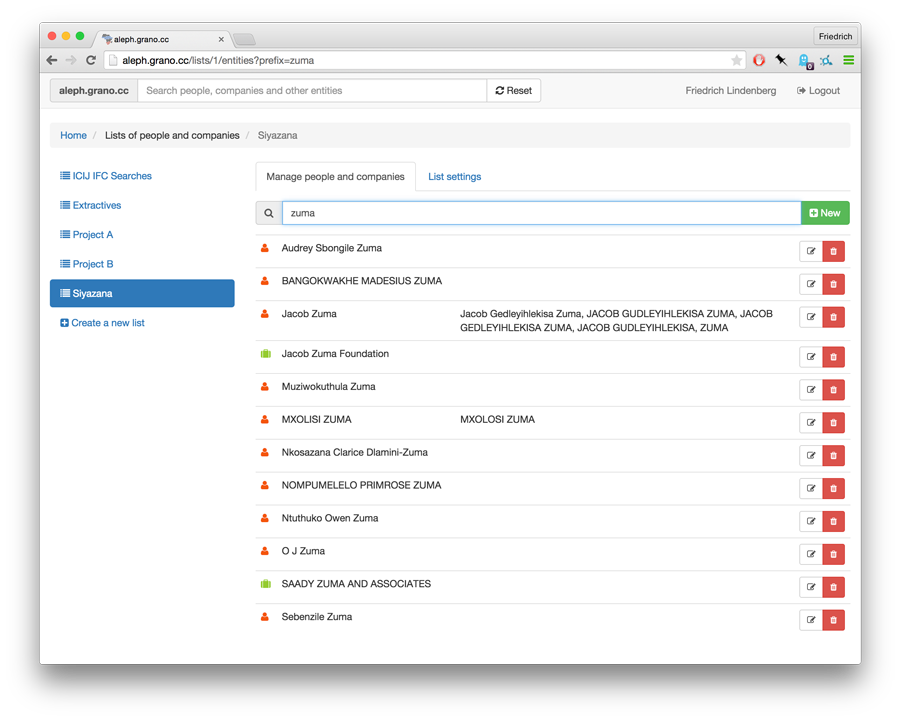

The resulting prototype, aleph (source code), allows users to easily perform those tasks through a simple web interface. Based on archivekit and loadkit, the tool maintains two distinct types of datasets: document collections and entity lists.

</a>

</a>

Document collections can be sourced from a wide range of locations; existing crawlers include DocumentCloud, SEC EDGAR, World Bank project documentation, SAFLII court cases and a small set of media sites. In the future, I’m hoping to provide support for Dropbox as a simple way for journalists to include their local document collections.

Each document imported from one of these sources is tagged against the entities present in aleph’s entity lists. Rather than relying on an out-of-the-box entity extraction service like Reuter’s Calais, entity lists allow researchers to name more specific sets of things they might be interested in: local parliamentarians in a country, companies and directors relevant to a particular investigation etc.

</a>

</a>

While lists were intended to be focussed on companies and people, they also work as “saved searches”. For example, a list might bundle search terms relevant to a particular investigation. This makes it easy to look up documents mentioning these terms repeatedly.

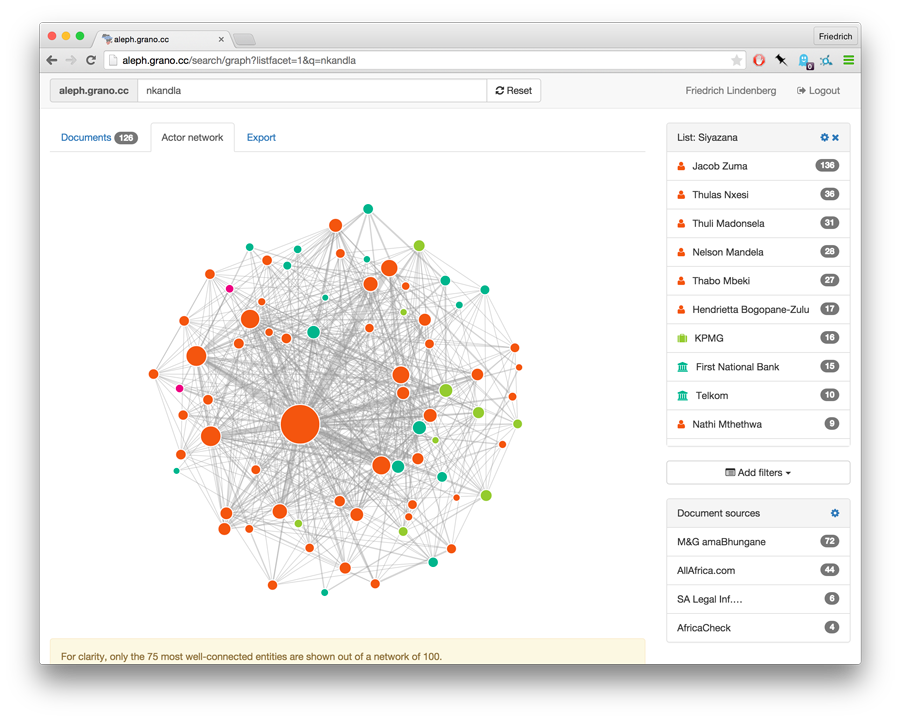

Finally, aleph also experiments with different ways of presenting the matching documents to it’s users. While a network graphing tool can be used to see which entities share mentions in a great number of documents, the most useful feature of the application is far less visual: an Excel export for result lists.

This way, a researcher can apply a set of filters to the document list and then download all matching documents to work through them and document their findings in the same spreadsheet.

</a>

</a>

While still in it’s infancy, aleph has proven a useful tool to quickly index and sift through a stash of documents. Future improvements should include email match notifications, as well as an integration with a more flexible toolkit for managing entity data - such as nomenklatura.

Connecting document mining tools

A visit to OCCRP’s Sarajevo office in early May allowed me to catch up with Jonathan and Adam, developers of the Overview project, and Smari, who is in charge of developing the Investigative Dashboard. Both tools aim to satisfy similar use cases to aleph, and we spent a good bit of time comparing our understanding of these user needs.

The question of how we can best link up these document mining tools to complement each other, however, is wide open. It would be desirable for a set of extracted documents to be able to travel from one tool to the next, including DocumentCloud (which is strong on presentation) and Harlo’s upcoming Unveillance project (which appears to be focussed on generating topic models).

Two starting points, however, are already visible: first, Overview has implemented a simple plugin system for it’s user interface so developers can make visualisations and filters for document sets (I hacked up a regular expressions filter in Sarajevo).

Second, Marcos and I came up with the idea of a document processing centipede during MozFest: document processing would be done through a series of independent web services that focus on providing specific bits of functionality (such as text extraction, entity tagging, date and place extraction, etc.). This would require some level of consensus on document metadata, which is also necessary to connect crawlers across different systems.

Yet, with all of these tools in place, I’ve still spent the last few evenings staring at a black console window hacking up scripts for a new project. Making sure a document set is exactly as requested by investigative researchers takes a lot of manual adaptation - and I think that archivekit, scrapekit and loadkit will be useful components in that toolbox for the next few years. Give them a shot and don’t be shy to file bugs and make modifications!